Red Sun, Golden Rose: The Heraldic Identity of The Medieval Academy of America

Red Sun, Golden Rose: The Heraldic Identity of The Medieval Academy of America

Dr. Chad M. Krouse

The Medieval Academy of America was formally incorporated on December 25, 1925 with a stated mission to, “conduct, encourage, promote and support research, publication and instruction in Mediaeval records, literature, languages, arts, archaeology, history, philosophy, science, life, and all other aspects of Mediaeval civilization, by publications, by research, and by such other means as may be desirable, and to hold property for such purpose.” [1] While the purpose and mission of the new scholarly enterprise was now clear, its visual identity would need to be addressed.

The Committee on Insignia, chaired by Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942), presented its report to the Academy’s president and council on April 29, 1927 with a recommendation to adopt a newly designed coat of arms for the insignia. [2] Cram enlisted his friend and colleague Pierre de Chaignon la Rose (1872-1941) from Harvard for the design, as the pair collaborated on numerous heraldic commissions early in their careers. [3] Once referred as the “Herald from Harvard,” la Rose became the nation’s leading authority on heraldry and singularly credited for its revival in the US during the early 20th century. [4] Given the Academy’s short-lived history, la Rose would need to draw from multiple sources in order to construct an identity visually matching the Academy’s bold mission.

La Rose readily cautioned new clients regarding the purpose of heraldry, attempting to combat what he called, “heralditis,” or an overly romanticized view of heraldry pervasive in the American mindset. [5] The primary purpose of heraldry is to provide identification of an individual, an essential need as knights clad in heavy armor on the battlefield required unhesitating assurance of their opponent’s identity. Citing the foundational canon whenever he could, la Rose stated, “arma sunt cognoscendi causa, writes the mediaeval jurist, Bartholus de Saxoferrato, or as the much later Guillim puts it: arma sunt distinguendi causa.” [6] Armorial bearings, in other words, served as an early form of medieval branding by creating a permanent connection between the shield’s design and its owner–the forerunner to the modern-day concept.

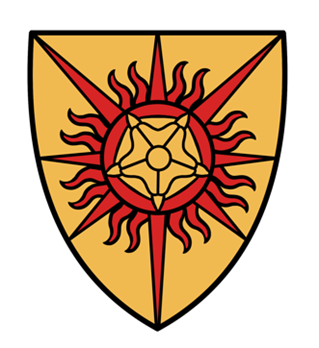

Rendering clear and perspicuous designs for arms, while adhering to the rigid customs and rules of heraldry, is no easy task. Yet, la Rose’s artful creation for the Academy demonstrated his mastery of the subject; by weaving together historical themes intertwined with aims and aspirational goals, la Rose layered meaning, purpose, and depth in a straightforward manner. Cram’s report detailed la Rose’s rationale for the design:

“The arms I have prepared for the Mediaeval Academy are based upon the following considerations. Perhaps the two greatest figures of the Middle Ages, from the point of view of lasting influence, are St. Thomas Aquinas and Dante. In Christian iconography the ‘attribute’ of Aquinas is a flaming sun and the culmination of Dante’s vision is the mystical rose. Combining the two symbols in a simple heraldic ‘coat’—and all good Mediaeval heraldry is exceedingly simple—we have an emblem that may well stand as a cognizance for the Academy.” [7]

La Rose added that the sun not only dispelled the darkness caused by the former “Dark Ages,” but illustrated the powerful enlightenment that would spread as a result of the Academy’s work. As for the rose itself, la Rose wrote, “is expressive of sheer beauty as achieved through poetry and the fine arts—the fine flower of the aforementioned enlightenment.” [8]

The red sun and metallic gold are two distinctive elements drawn from the attributed arms of St. Thomas Aquinas, and la Rose would employ the pair again in his design for the Institutum Divi Thomae in Cincinnati. [9] Even more curious, la Rose proposed a nearly identical coat to the Academy’s arms in 1939 for St. George’s School in Middletown, Rhode Island. La Rose’s proposal showed a red sun—albeit with the tips of the rays pointing dexter (left) rather than towards sinister (right) as in the Academy’s arms—charged with a gold book opened and inscribed with the motto veritas, all set upon a silver field. [10] If the sun is attributed to Aquinas, the proposal ignored the splendor of the red cross ascribed to the school’s dedication of St. George while confusing corporate identity altogether. [11] In the end, St. George’s School adopted la Rose’s second proposal incorporating the red cross and eliminated any possible confusion with the Academy’s arms.

The blazon, or written description of the shield’s composition, for the arms of the Medieval Academy of America given by la Rose is: “Gold, on a sun gules a rose of the field.” [12] La Rose’s design for the Academy represents the best in American heraldry–both in form and aesthetic. Through the abstract imagery of heraldry, the Academy’s arms have provided more than mere visual identification, they have become a cherished symbol of excellence in medieval scholarship the world over.

The genius of la Rose’s design philosophy, exemplified through the Academy’s arms, has ultimately produced timeless identities for hundreds of organizations bearing his work, and many of his armorial designs are still used today. [13] In April 2027, the Academy’s arms will celebrate a highly respectable 100th birthday, a testament to the visual power of identification which heraldry continues to enjoy well into the 21st century.

[1] Coffman, George. “The Medieval Academy of America: Historical Background and Prospect.” Speculum 1, no. 1 (January 1926): 17.

[2] “The Report of the Committee on Insignia” (29 April 1927), Archives of the Medieval Academy of America, Boston, MA.

[3] Following his highly criticized article on the subject, Cram would bow to la Rose as the expert on all matters of heraldry. See Cram, Ralph Adams. “The Heraldry of the American Church.” The Churchman 83, no. 26 (29 June 1901): 813-818.

[4] Galles, Duane. “The Reform of Ecclesiastical History Revisited.” The American Benedictine Review 43, no. 4 (December 1992): 414-428. La Rose never referred to himself as a herald, but rather an archeologist.

[5] La Rose, Pierre de Chaignon. “Ecclesiastical Heraldry-And Architects.” Liturgical Arts 2, no. 4 (Fourth Quarter, 1933): 190.

[6] La Rose, “Ecclesiastical Heraldry-And Architects,” 187.

[7] “Report Committee on Insignia”

[8] “Report Committee on Insignia”

[9] Painting of arms for the Institutum Divi Thomae (1936), CUA 116, Box 1, Archives of Catholic University, Washington, DC. The institute’s arms are blazoned: Or, on a cross Gules an open book edged with two clasps Or inscribed Religio Scientia between four bezants and in dexter chief a sun Gules.

[10] Preliminary sketch (1939), La Rose Box 5, Archives of St. George’s School, Middletown, RI. The blazon for the preliminary sketch: Argent, on a sun Gules an open book edged with two claps Or inscribed Veritas. The school rejected the preliminary proposal and adopted la Rose’s second design which was a heraldic cant, or pun, on the founder’s surname and blazoned: Lozengy Sable and Argent, overall a cross Gules.

[11] Based on the author’s collected data, by 1938 la Rose began his final journey, as illness forced him to ignore multiple requests for heraldic commissions.

[12] Ralph Adams Cram to John Marshall, April 29, 1927, Archives of the Medieval Academy of America, Boston, MA. A modern blazon for these arms would read: Or, on a sun Gules a rose of the field.

[13] Through the author’s ongoing research, more than 250 designs for corporate arms have been identified and attributed to la Rose.

About the Author:

Dr. Chad Krouse is a member of the Board of Governors of the American Heraldry Society and actively researching the life and heraldic work of Pierre de Chaignon la Rose (1872-1941) in anticipation of a book. Krouse’s research on la Rose was recently accepted for the 36th International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences to be held in Boston, September 2024, and will later be published in Genealogica & Heraldica.

Krouse earned a Bachelor of Arts from Hampden-Sydney College, a Master of Divinity degree from Sewanee: The University of the South, and his Doctor of Education degree from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU).

With 16 years of service in higher education philanthropy, Krouse is the assistant vice president for university development at VCU. Krouse has presented nationally and served as an adjunct professor at the College of William & Mary’s School of Education and the VCU L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs. He lives in Richmond, Virginia.

About the MAA Archives:

As we head towards our Centennial in 2025, we are digitizing the MAA Archive and will make much of our historic material available in an open-access repository in the coming months. The MAA Archive is a treasure-trove of material pertaining to the history of Medieval Studies in the twentieth century. If you are working on the historiography of Medieval Studies in North America, you may find this material to be a rich resource. To learn more, please contact Executive Director Lisa Fagin Davis (LFD@TheMedievalAcademy.org).